Jump ahead

What is sashiko

Sashiko is not quite what you'd call classic embroidery. It's actually much closer to quilting. A simple running stitch joins layers of cloth, sandwiching them together, and creating a decorative motif almost as an afterthought. If you have ever tried quilting, stitching together front and back layers with batting in the middle, you can probably get your head around it. In fact, historically, sashiko was used primarily for double or triple layers of fabric.

The best fabric, the one of highest quality, was always on top. The batting was made up of older, worn-out bits of fabric. As the layers were stitched together, a quilted pattern emerged.

So, what was sashiko for? Originally, the technique served multiple functions. First off, the additional layers reinforced an article of clothing that needed mending and made it warmer. As a sort of bonus, its decorative elements dressed up a well-loved garment.

How sashiko mending started

The technique spread through rural Japan in the Edo era (1615–1868), a time of relative prosperity and peace. Sashiko became a vital part of the rural economy. In the winter, when there was little to do on the farm, young women and girls set off for local schools to learn sewing, weaving, dying, and spinning. The study of sashiko also instilled characteristics highly valued in traditional Japanese culture: patience and dedication.

At this time, all thread was spun by hand, a demanding process, just like cloth weaving and dying with indigo. Old textiles were simply not something you tossed aside. When fabrics were worn out, they found their way into the inner layers of new garments or were used to make working clothes.

The upper layer was usually made of newer material (depending on how well off the wearer was). Fabric was generally made of linen, hemp, and ramie. Every scrap was put to use for aprons, sacks, pockets, and cleaning rags. Every bit of fabric had its worth.

Why blue and white?

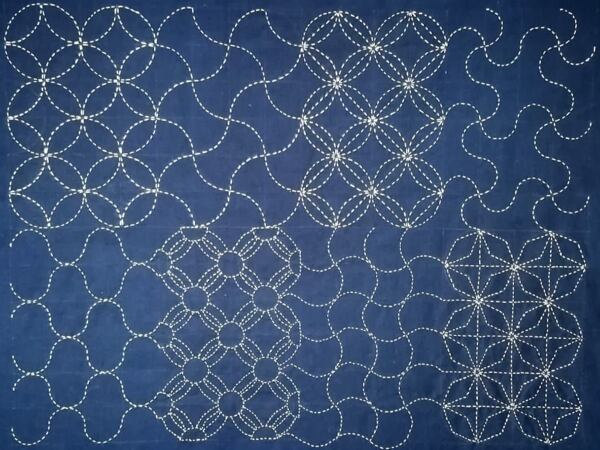

Traditionally in Japan, sashiko was done in white thread on dark blue cloth dyed with indigo (Indigofera tinctoria). This preference dates to the Edo era, when the lower social orders could not wear bright colors or loud patterns.

With time, the white stitches took on the blue of the indigo dye from the base cloth, turning a pale blue. As a result, light blue thread came to be a popular choice, yielding a blue-on-blue effect.

Sashiko patterns as talismans

It is fascinating how individual sashiko patterns emerged and changed. Tracing the development of a single pattern can be a neat piece of detective work. Each design has its own name and an interesting backstory anchored in Japanese history.

Many patterns served mystical, protective functions. So you'll see a particular design, takonomakura, used on the clothing of fishermen to ward off shipwrecks. Others, like firefighters, had their own talisman patterns.

Three, five, and seven are lucky numbers and often appear in sashiko patterns. Paired or doubled motifs are common in wedding patterns.

Sashiko meaning today

The arrival of mass-produced synthetic materials had a major impact on sashiko. In the first half of the 20th century, there was a shift in how people dressed in rural areas and the use of sashiko dropped. Old, worn-out bits of textile lost their value and people stopped recycling them.

Fortunately, enough people continued to harbor respect for traditional ways of doing things, so that today we still have a large historical collection and a wellspring of patterns. It's interesting that the resurrection of sashiko in Japan dates to the 1970s with the arrival of the quilting craze from the West.

Sashiko is experiencing a major revival. Though recycling and thrift are no longer a matter of sheer survival, sashiko stitching has become a creative activity, a source of relaxation, sometimes even a form of therapy.

Sashiko patterns

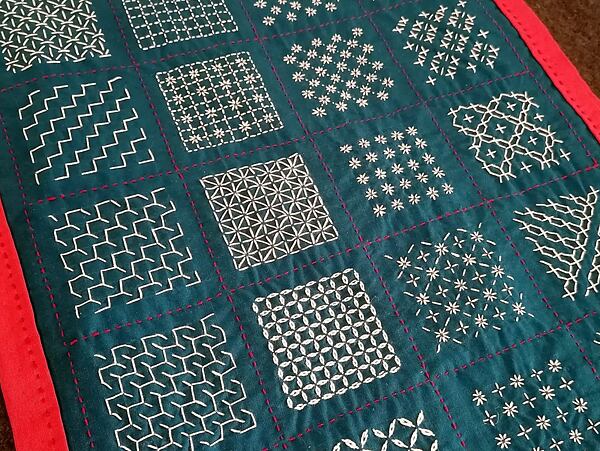

Sashiko encompasses several stitching techniques, each with its own pattern style, specifications, and rules. The patterns fall into two main groups: sashiko Hitomezashi and sashiko Moyozashi.

Hitomezashi sashiko

Hitomezashi (one-stitch sashiko) is typical for Shonai in Yamagata prefecture. It is based on straight lines, where stitches meet or cross, creating a pattern. Some motifs of this type bring to mind the traditional European embroidery known as blackwork.

Moyozashi sashiko

Moyozashi, on the other hand, features a running stitch set in curves and straight lines that change direction to create an overall pattern. The individual motifs never cross or overlap. Unbroken lines and doubled thread help make the final piece thick and warm.

They say the devil is in the details. In Japanese needlework, even the humble knot is treated differently. It is fascinating to see how various cultures have various ways of approaching a problem in textile production. There are patterns that do not use a knot at all, so the problem of what to do when you come to the end of the thread is handled differently, elegantly, with back stitching or some other trick.

What you need for sashiko

Sashiko fabric

Most sashiko uses sturdy, good quality cotton fabric. You can choose a solid or a print. The absolute classic is a solid cotton dyed with real indigo.

Sartor carries authentic Japanese fabric printed with sashiko templates to help you get started (the printed template washes out in warm water).

Sashiko thread

Sashiko thread is spun especially for that purpose. Cotton came into use in Japan in the 17th century and today it is the most common choice. The thread comes in three weights – fine, medium, and heavy. Your choice depends on the size of the pattern you want to make.

Japanese sashiko thread has a stronger twist than ordinary embroidery floss.

Sashiko needles

Sashiko needles are longer and sturdier than classic embroidery needles. This lets you pierce multiple layers of fabric comfortably and lay down more stitches at once, a common technique in sashiko.

Thimble

There are two types of thimble in Japan, and they are used differently than what you may be familiar with. This is due to how the needle is held and manipulated for sashiko. You'll only need a thimble if you're working with several layers – for projects with one or two layers there's no need.

Scissors

Japanese scissors are simple and super sharp. You can see them in the photo below. I've been using them for years now – they're so precise. They're great for lace making and other types of embroidery too.

What else

Other things you'll need for sashiko include a ruler and a white chalk pencil (if using dark blue fabric) or a fabric marker (if working on a light-colored fabric).

For sashiko you don't need an embroidery hoop. The fabric is held in your hands so that you can make multiple stitches at once. It's important to master this way of working because it is helps you to lay each stitch properly.

How to learn sashiko

There are plenty of books in English and a growing number of tutorials online. Personally, I've learned the most from Japanese publications and Japanese teachers. My guide in discovering sashiko has been Kazue Yoshikawa, a Japanese teacher of this technique. You can find her online at Sashiko.lab.

Visit a workshop

There's no better way to learn sashiko than to sit down with an expert and get hands-on instruction. Look for a sashiko workshop in your area. We recommend looking for an instructor with experience and an understanding of Japanese culture.

If you happen to be in Prague, check out Sartor's workshop calendar. Our sashiko workshops (presented by the author of this article) attempt to present an authentic experience for learners in the heart of Europe, thousands of miles away from the island where this art form originated. (Note: You'll get the most out of the workshop if you are able to communicate in Czech or Slovak.)

Get started with a kit

If this article has piqued your interest and you want to try sashiko, there's no better time than the present. We stock a number of sashiko kits that have everything you need for your first piece.

These sashiko starter kits include fabric with a wash-out sashiko template, special sashiko thread, a sashiko needle, and easy-to-follow instructions (in Japanese, but with illustrations). The pre-printed templates mean you don't have to sketch your own design (something you would learn in a workshop), so it's almost as easy as painting by numbers. It's a great way to get your feet wet and decide if sashiko is for you.

Comments(0)